Common Brown

Heteronympha merope merope (Fabricius)

Interesting Aspects

The Common Brown is probably the main butterfly associated with the exclamation of many people, "Where have all the butterflies gone? They used to be everywhere when I was a child!" This butterfly used to be particularly common in woodland settings in the Adelaide Hills and along the hills face, flying through the understorey or congregating in large numbers on flowering bushes to feed. With the increased pressures of urbanisation and agriculture, and also due to the fear of bushfires and snakes, many native grassland settings for this butterfly have disappeared near Adelaide, and consequently this butterfly has also decreased in numbers. If some grass areas were left uncleared during the annual bushfire preparation, (rather than a total clearance), then this butterfly would recover rapidly.

It is a very interesting butterfly which, like its sister species the Wonder Brown (Heteronympha mirifica) confined to the eastern states, has adapted well to the browning (loss of forests) of Australia since the Miocene geological time period (20 million years BP), having evolved from the more primitive members within the Heteronympha group. The sexes are strongly dimorphic (different appearance), and along with H. mirifica are the only satyrs in Australia to exhibit this morphology difference. The male has silvery-grey sex brand patches on the uppersides of all wings. Both male and female butterflies sometimes also occur in melanic dark forms, particularly in cold mountainous areas of the eastern states of Australia, and this is possibly thermoregulatory related. In South Australia the females occur in two colour forms in which the hindwing underside is either yellowish or purplish. In the Adelaide area the purple form is more common, while in the Lower Southeast Region the yellow form is more common.

Both sexes start emerging in mid-spring (the males slightly earlier), the females mate and then go into hiding (aestivate), and they continue to do so until the following early autumn, some four months away. During this aestivation, the females may occasionally fly during the early mornings or late evenings, or on cool overcast days, particularly to suck on moisture, but do not actively feed from flowers during the day. Their abdomens are full of fat tissue which they live off through the summer months. Although fertile, they remain in a non-gravid state (eggs not developed) until the early autumn. Egg development and laying then commences, with the result that young larvae (especially in the drier temperate areas of Australia) are assured of a good supply of young grass shoots stimulated by mid-autumn rains. Females will also start to feed from flowers in early autumn, and in some cool areas such as in the Lower Southeast of the state, hundreds of them can be seen feeding during the day from scabiosa flowers growing along the edges of roads and pine plantations. A clap of the hands will cause these females to explode off the flowers into a cloud of flying butterflies, but they quickly drop back onto the flowers.

When active, the butterflies have a particular liking for moisture and on hot days are readily attracted to garden sprinklers. The rare mid-summer rain shower will even bring females out from hiding. Both sexes are attracted to seeping gum from tree wounds and fermenting fruit, and during the wine making season the females are attracted to the alcoholic dregs and pressings in large numbers. Both sexes are also attracted to sugary secretions of large aggregations of scale insects on trees, where they can be so intoxicated with the feeding that they can be lifted off the scale by hand. When not feeding, the males actively try to seek out the aestivating or newly emerged females, by flitting close to the ground or searching every nook and cranny. Disturbed, fertile females will reject males by lying on the ground with closed wings. The males sometimes congregate in large numbers when feeding on a favourite flowering plant, and the 3 m flowering stalk of some yacca grass trees (Xanthorrhoea) can literally drip with butterflies. They are also partial to flowering tea-trees growing along creek lines, (such as occur at Morialta Conservation Park), on Christmas bush (Bursaria), and on the purple flowers of Scabiosa. On very hot days the butterflies will congregate in cool, shady areas.

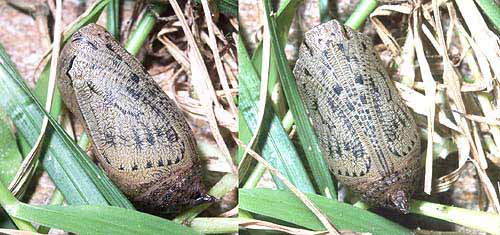

The butterflies have an irregular flight, and prefer to settle on or near the ground. Like most satyrs, the wing undersides are cryptically camouflaged, and it is very difficult to detect these butterflies when they are settled with wings closed and erect, owing to their close resemblance to the ground, or to dead leaf and plant debris. The butterfly is one of the first to fly in the morning, and one of the last to finish flying in the afternoon. It will also fly on heavy overcast days, and sometimes even in drizzle. Males will hilltop, particularly late in their flight season.

Both sexes are normally very timid when not feeding at flowers, and can only be approached with extreme care. Females can be less timid during their aestivation period. Recently, a crew on a fishing vessel going about their business near the edge of the continental shelf some 26 km south of Cape Gantheume on the south side of Kangaroo Island, reported a male fly pass heading south towards Antarctica!